Mushrooms have been used as both food and medicine since antiquity. One of my favorite poems, discovered in an ancient Egyptian temple, illustrates this history: “Without leaves, without buds, without flowers, yet from fruit; as food, as tonic, as medicine: the entire creation is precious.” At a time when viral epidemics are inevitable and the current COVID-19 pandemic has presented in most of the world, antiviral therapies are possibly being investigated now more than ever before. This paper explores the use of medicinal mushrooms as antivirals in in vivo (human and animal) and in vitro (petri dish) experiments and how these experiments may inform us on the utilization of these fungi as antiviral therapies.

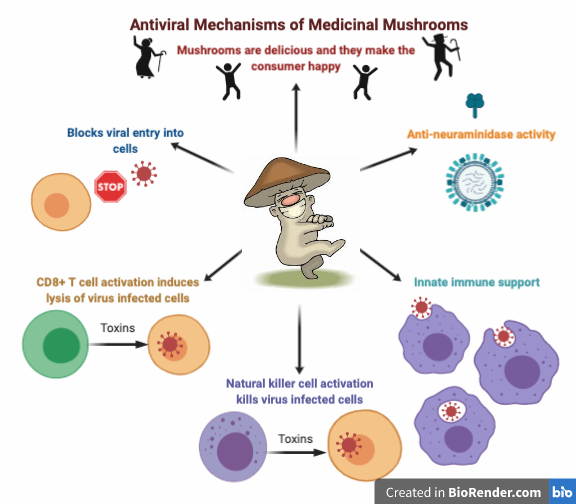

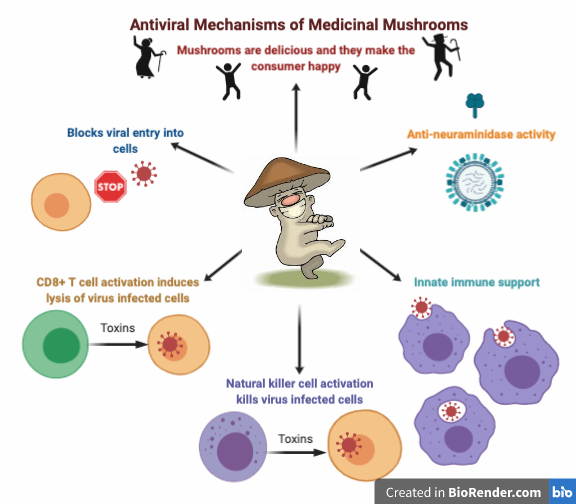

Medicinal mushrooms are known as biological response modifiers. This physiologic modification is largely a result of the interaction of various mushroom constituents, primarily polysaccharides, with the immune system. Therefore, to understand the role that medicinal mushrooms play as antiviral agents, it is imperative to understand the happenings of the immune system in response to a viral pathogen and the interplay between mushrooms, their constituents, and this system. Unlike pharmaceutical antivirals, the actions of medicinal mushrooms are not straightforward, and there is no absolute rule that mushrooms stimulate or depress immunity. Mushrooms contain many constituents and are dynamic in their interplay with the human body.

Overview of anti-viral immunity

The initial immune response to a new pathogen is facilitated by the innate immune system (innate meaning inborn or natural). This is our first response to non-self organisms, and requires no other stimulation than the pathogen itself. It is the response that is ready to go at all moments in the day and persistently protects the human body from infection. It is easy to imagine that an altered or defective innate immune response can have a detrimental effect on the ability to fight disease.

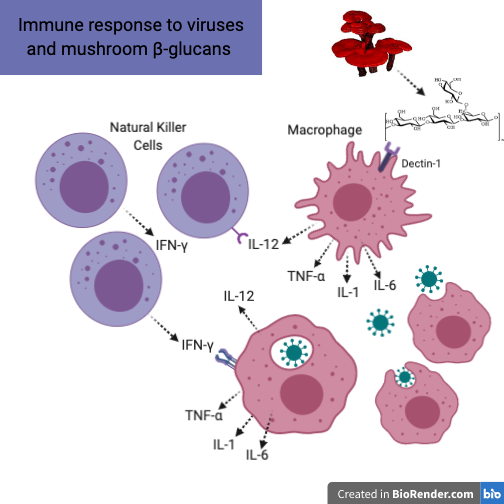

The innate immune response to a virus is multidimensional. There is a massive amount of cell-to-cell communication and different chemicals (called cytokines) are released to make this communication possible. Once an epithelial cell (cells that make up the surface of different body tissues like skin, lungs, etc) is infected with a virus, Type 1 Interferon (Interferon-α, a cytokine) is released and has three major functions: to induce resistance to viral replication in all cells, to increase expression of ligands for receptors on natural killer (NK) cells, and to activate NK cells to kill virus infected cells. NK cells are lymphocytes (a small white blood cell that is found primarily in the lymphatic system) that defend against viral infections and tumor cells via cytokine stimulation and direct killing of infected cells. NK cells provide such a vital role in antiviral immunity that people deficient in NK cells suffer from persistent viral infections. These functions of NK cells are important in regards to understanding medicinal mushrooms and their role in antiviral immunity.

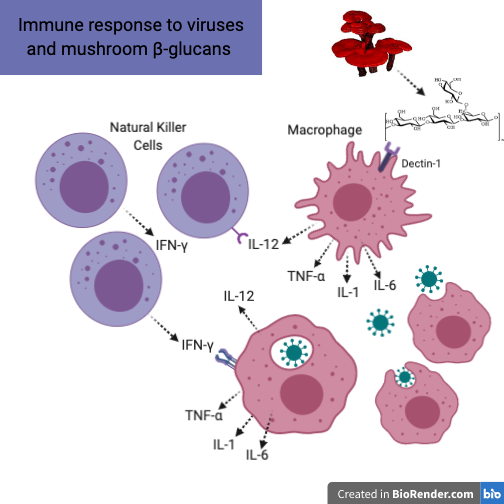

Imagine the immune response to a newly inhaled viral particle. This virus enters the healthy person’s lungs and invades the lung epithelium. Once an epithelial cell is infected, it releases Type 1 Interferon, which turns circulating NK cells into cytotoxic effector NK cells (NK cells primed to seek out and kill virally infected cells). The cytotoxic effector NK cells promptly start the process of seeking out infected cells and the innate immune response commences. At the same time, there are resident macrophages in the respiratory epithelium and throughout the body. These macrophages (“big eaters”), are also major players in the innate immune response. Their role is to consume these virus particles and produce chemicals (cytokines and chemokines) that attract and engage more NK cells and also T cells. An important cytokine engaged in this process is interleukin-12 (IL-12), which stimulates NK cells to not become cytotoxic, but rather effector NK cells. Unlike cytotoxic effector NK cells, these effector NK cells stimulate an inflammatory response via Type 2 Interferon (IFN-γ), at the site of infection. This inflammatory cascade consists of IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-12, and is essential for viral eradication. It is only when this response is out of control that it becomes problematic and detrimental to the host.1,2,3,4 If this initial response is not primed for viral combat, viral particles continue to proliferate and infect more healthy cells. It is in this phase that medicinal mushrooms can have a great impact to prevent viral infections from taking over the host.

| Cytokine |

Source |

Role |

| IFN-α |

Virus infected epithelium |

Circulating NK cells –>Cytotoxic effector NK cells |

| IL-12 |

Macrophage post virus consumption |

NK cells –> effector NK cells |

| IFN- γ |

Effector NK cells |

Macrophages –> inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-2, IL-1, IL-6) |

| TNF- α |

Macrophages |

Induces blood vessels more permeable, enabling effector cells to enter infected tissue |

| IL-1 |

Macrophages |

Induces blood vessels more permeable, enabling effector cells to enter infected tissue |

| IL-6 |

Macrophages |

Induces fat and muscle cells to metabolize, make heat and raise temperature of infected tissue |

| IL-12 |

Macrophages |

Recruits and activates NK cells –> secrete more cytokines that strengthen macrophage response to infection |

| IL-10 |

Toxic substances secreted by macrophages–> TH2 |

Suppress macrophage activation |

| IL-4 |

Toxic substances secreted by macrophages–> TH2 |

Suppress macrophage activation |

COVID-19 is an excellent example of these two main immune responses.5 The first stage of infection is the less severe incubation phase. The previously mentioned immune response is imperative to eliminate the virus and keep disease from progressing to later, more severe stages. It is in the incubation stage that immune-stimulating therapies are most indicated. In more severe stages, the protective immune response is impaired and the virus will spread and destroy healthy cells. Because damaged cells induce inflammation, immune stimulation is less indicated and it is more favorable to treat with anti-inflammatory therapies. It is at this stage of disease, characterized by severe lung inflammation, that life-threatening respiratory disorders occur and the feared cytokine storm is initiated. The cytokine storm is an influx of inflammatory cytokines. It is an overdramatic immune response that is harmful to the host and can often lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome. The inflammatory cytokines that are so important for stage one of the disease ( IL-1, IL6, TNF-α, and IL-12) are now abundant, destructive and out of control.6,7

The two phase division of the immune response is very important . The first immune response is protective and a response that can be altered through diet and lifestyle: our base response when initially combating infection. As mentioned previously, this is the phase where medicinal mushrooms are most indicated. They are primers of the first response to viral particles.

Antiviral immunity in healthy adults

The most informative studies exploring the interaction of medicinal mushrooms and the immune response are done on healthy human adults. In these studies it is ideal to see cytokine and NK cell levels before and after mushroom intake in healthy people to get a good idea of how exactly the mushrooms are priming our innate response. There are not many studies of this kind, but there are a few.

Healthy Korean men who took 1.5g/day of powdered extract of Cordyceps militaris brown rice culture for four weeks had their blood analyzed before and after treatment. Levels of NK cells, IFN-y and IL-12 were examined in blood samples before and four weeks after therapy began. There was a significant increase in NK cells and IFN-y and no difference in IL-12.8 Cordyceps sinensis mycelium extract, in combination with the endoparasitic fungus that commonly exists with C. sinensis, Paecilomyces hepialid, also had immune-stimulating activity in healthy adults. In this study, people were given 1.43g/day and after eight weeks the cytotoxic activity of NK cells was significantly higher than at baseline (before therapy.)9 Wild fruiting bodies of Cordyceps species are incredibly expensive and are therefore rarely, if ever used in research. However, It is likely that cultivated fruiting bodies have similar medicinal qualities.10,11,12

Another study with 52 healthy males and females aged 21-41 consumed either 5g or 10g of Lentinus edodes (shiitake mushroom) daily for four weeks. Eating the Shiitake for four weeks led to increased proliferation of NK cells and IgA, decreased CRP (a marker of inflammation), and an increase in IL-4, Il-10, TNF-α and IL-1. Serving size had no impact on cytokine levels, except that two servings of Shiitake increased serum IL-4.13 Shiitake is a good example of the dynamic effects that some mushrooms have on the immune system. Shiitake both increased inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, TNF-α) and anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10 and IL-4) simultaneously, illustrating the use of the term immunomodulatory: it is neither a pure stimulator nor a depressor of the immune system. This may mean that immune modulating mushrooms are safe and effective to take during both phases of the viral immune response, and in fact, may have inhibitory effects during the cytokine storm of acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Grifola frondosa (Maitake) also exhibits this modulating activity. G. frondosa fruiting body extract produced both immune stimulatory IL-2, TNF-α and IFN-γ and suppressive IL-10 in breast cancer survivors taking 5-7g/kg per day of mushrooms extract for three weeks.14

The combination formula of Trametes versicolor(Turkey tail) and Salvia miltiorrhiza  (Red sage root, or Dan Shen) given at 50mg/kg and 20mg/kg respectively for four months showed significant immunomodulatory effects in healthy adults. There was a significant increase in PBMC (peripheral blood mononuclear cells – NK, B and T cells) gene expression of IL-2 receptor, increase in T helper cells and the ratio of T helper cells to cytotoxic T cells. There is also a significant increase in IFN-γ.15 There is little information in western herbal and mycological medicine about the use of plant and mushroom combination formulas. Dan Shen is known to ‘move the qi of the blood’ and in combination with the immune stimulating activity of Turkey tail, has promise as a very useful combination for immune therapy.

(Red sage root, or Dan Shen) given at 50mg/kg and 20mg/kg respectively for four months showed significant immunomodulatory effects in healthy adults. There was a significant increase in PBMC (peripheral blood mononuclear cells – NK, B and T cells) gene expression of IL-2 receptor, increase in T helper cells and the ratio of T helper cells to cytotoxic T cells. There is also a significant increase in IFN-γ.15 There is little information in western herbal and mycological medicine about the use of plant and mushroom combination formulas. Dan Shen is known to ‘move the qi of the blood’ and in combination with the immune stimulating activity of Turkey tail, has promise as a very useful combination for immune therapy.

Not all fungi are created equally as immune modulators. When the β-glucan isolate, lentinax, from L. edodes mycelium was administered to healthy adults, there was no difference seen in NK cells and inflammatory cytokines between treatment and control groups.16 This juxtaposes the previous Shiitake study where the subjects consumed whole mushrooms and did have immune stimulatory effects. Contrary to what has been suggested in in vitro research 17,18 a mushroom that showed no benefit in vivo was Agaricus blazeii. Healthy elderly women consumed 300mg of A. blazeii fruiting body extract three times daily for 60 days, and there was no change in levels of IFN-γ, IL-6 and TNF-α after administration.19 Perhaps the dose was too low in this study, further research is needed.

| Mushroom |

Cytokine response |

Immune response (simplified) |

Phase of viral response most applicable |

| Grifola frondosa (Maitake) |

IL-10

IL-2, TNF-α, IFN- γ |

Anti-inflammatory

Pro-inflammatory |

Possibly severe phase

Prevention/incubation phase |

| Lentinus edodes (Shitake) |

IL-4, IL-10

TNF-α, IL-1 |

Anti-inflammatory

Pro-inflammatory |

Possibly severe phase

Prevention/incubation phase |

| Cordyceps spp. |

IFN- γ |

Pro-inflammatory |

Prevention/incubation |

| Trametes versicolor (Turkey tail) with Salvia miltiorrhiza (Red sage) |

IL-2, IFN- γ |

Pro-inflammatory |

Prevention/incubation |

Mushrooms as immune-modulators

The increases seen in IL-10 and IL-4 after Maitake, Shiitake, and Cordyceps mycelium intake are important as they relate to TH2 immune responses. TH2 responses are anti-parasitic and anti-allergic, but through the lens of viral immunity and inflammation, are anti-inflammatory. In fact, IL-10 is considered an anti-inflammatory master regulator. 20,21,22,23 IL-10 is essential for defending the host from tissue destruction during acute phases of immune responses, though it is not as desirable in the initial phase of infection, where a higher TH1 (inflammatory) response is required. At this stage, IL-10 can downregulate antigen presentation in macrophages and dendritic cells and can lead to chronic infection.24 During the later stages of infection, however IL-10 levels can determine host survival and higher concentrations of IL-10 have been associated with better outcomes in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome.25

This is immune modulation. As depicted, mushrooms are neither solely inflammatory, nor anti-inflammatory, and so should be utilized as such. The safety of medicinal mushroom use at different phases of the immune response is debatable. It is most likely that if mushrooms and mushroom extracts are consumed as preventative medicine, and the immune response is primed, the host won’t succumb to infection in the first place. There is some concern that if IL-10 is too high during the initial phase, the infection will become chronic, but since the mushrooms are simultaneously stimulating inflammatory cytokines, this isn’t likely.

| |

TH1 |

TH2 |

| Associated cytokines |

IL-2, IL-12, IFN-γ, TNF-α |

IL-4, IL-10, IL-5, IL-6, IL-13, IL-9 |

Mushroom Derived β-glucans and the Immune Response

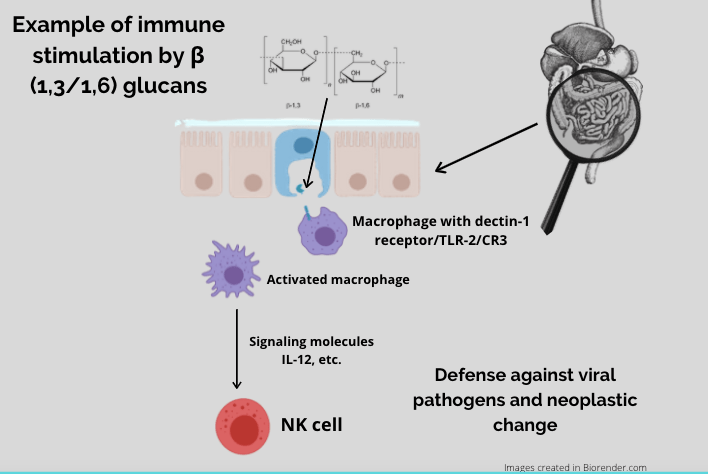

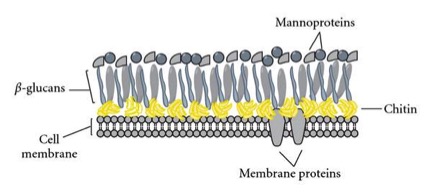

The most studied immune-stimulating constituents derived from medicinal mushrooms are 1,3/1,6-β-glucans. β-glucans, or polysaccharides, are present in all mushrooms as they are an integral component of the mushroom cell wall. Macrophages in the gut have specific receptors for β-glucans, most significantly Dectin-1, complement receptor 3 and TLR-2.26,27 When β-glucans bind to these receptors, an immune response is initiated. Because of this, in most studies, polysaccharides have been deemed the ‘active’ constituents in regards to immune activation. Therefore, isolation and administration of these compounds is most commonly seen in the literature.

Pleuran, a polysaccharide derived from Oyster mushrooms

There are a number of human trials exploring the use of pleuran, a polysaccharide extracted from Pleurotus ostreatus (Oyster mushroom) as a therapeutic agent in respiratory infections. As respiratory infections are most commonly of viral origin,28 it seems appropriate to discuss this research here. In a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized multicentric study, 175 children treated with pleuran experienced a significant reduction in the frequency of recurrent respiratory tract infections.29 These findings agreed with a Spanish study investigating 166 children aged one to ten years old who were also treated with pleuran for recurrent respiratory infection.30

Advantageous respiratory effects of pleuran are also observed in adult athletes. A study  of 50 athletes treated with pleuran over a three month period found a significant reduction in the frequency of upper respiratory tract infections compared to athletes treated with placebo. Blood samples of the athletes showed significantly higher levels of circulating NK cells in the pleuran group as compared to the placebo group.31

of 50 athletes treated with pleuran over a three month period found a significant reduction in the frequency of upper respiratory tract infections compared to athletes treated with placebo. Blood samples of the athletes showed significantly higher levels of circulating NK cells in the pleuran group as compared to the placebo group.31

Oyster mushrooms contain almost 33% polysaccharides,32 so we can deduce from these studies that consuming whole Oyster mushrooms and/or Oyster mushroom aqueous extracts could be beneficial for the prevention of respiratory infections.

Immune-stimulating polysaccharides in late stage cancer patients

The polysaccharides isolated from Ganoderma lucidum, also known as ‘Ganopoly’, were administered at 1800mg three times daily in late stage cancer patients, and there was a significant increase in NK cells, IL-1, IL-6 and IFN-γ after administration.33 Another isolate, polysaccharide krestin (PSK), is a protein-bound polysaccharide derived and isolated from Trametes versicolor. In a phase one clinical trial, breast cancer patients consumed 6 or 9g of PSK for six weeks, leading to an increase in CD8 T cells and NK cells.34 Another isolated polysaccharide, Maitake D fraction (derived from the fruiting body of G. frondosa), was administered to patients with stage 2-4 cancer aged 46-84 at doses between 40 and 150mg twice daily. IL-2 and NK cell activity was detected through peripheral blood draw and both were significantly increased after administration35 The research on isolated, mushroom-derived polysaccharides was intended to prove anti-cancer activity, but because of the close similarities of anti-cancer and antiviral immunity,36 it also suggests that polysaccharides support antiviral immunity in late stage cancer patients.

In vivo healthy animal trials

Polysaccharides from G. lucidum, L. edodes and G. frondosa administered to healthy mice significantly increase macrophage phagocytosis and NK cell activity.37 Other studies have demonstrated similar immune-enhancing effects on healthy mice with G. frondosa and L. edodes extracts exhibiting increases in IL-12, IL-6, and IFN-γ. In this study, the combination of the G. frondosa and L. edodes extracts have a stronger effect than either extract alone.38 Maitake D fraction increases IL-12 and IFN-γ in healthy mice along with a significant decrease in IL-4 and IL-10.39 C. militaris extract also increases IL-12 and TNF-α cell activity in H1N1 infected mice.40

In vivo animal cancer models

A number of in vivo animal trials explore different mushroom extracts with similar immune effects. Many of these animal studies are cancer models, so they will be mentioned briefly. Agaricus hot water extracts increase IFN-γ, IL-6 and IL-1,41,42 Reishi polysaccharide and triterpene extracts increase inflammatory NFkB, TNF- α, IL1-b, IL-2, IFN-γ 43,44,45,46 Maitake extract increases IL-12, IFN-γ and TNF-α, IL-147,48 and PSK increases IL-12.49 Ganoderma polysaccharides increase NK cells and cytotoxic T cells, IL-1, IL-6 and IL-1.50,51

Because these are cancer models, so it is not completely clear if the same effects would take place in healthy animal models, though we can deduct from other experiments using healthy volunteers and healthy animals that it is likely that similar immune effects would occur.

In vitro antiviral activity

There are a number of fungal constituents that have antiviral activity in-vitro, including polysaccharides, indole alkaloids, terpenoids, polyketides and lignan derivatives. Agaricus subfruescens and Grifola frondosa act directly on viral particles, β-glucan protein from A. subfruescens inhibits viral adsorption into the cell, polysaccharides from A. subfruescens and polysaccharopeptide from T. versicolor inhibit viral replication, and triterpenes from Ganoderma spp directly kill virus proteins.52

The fruiting body ethanol-water extract of T. versicolor extract increases the TH1-related cytokines IL-2, IL-12, IL-18 and IFN-γ.53,54 As most of the research done on T. versicolor is with an isolated constituent, PSK, it is significant that this study, which used whole fruiting body extract, exhibits immune stimulating qualities.

Maitake fruiting body extract does not show direct antiviral activity to influenza A but does exhibit antiviral activity through macrophage activation and an increase in TNF-α production. 55

L. edodes mycelium directly inhibits influenza virus growth at early phases of infection, possibly during the entry process of viral particles to host cells. The in vivo administration stimulated an increase in innate immunity as well, suggesting that Shiitake mycelium has antiviral effects through both inhibition of initial viral replication and immune stimulation.56

A little known mushroom, Cryptoporus volvatus, the Cryptic Globe Fungus, has shown  anti-viral activity through multiple mechanisms. Aqueous extracts of the fruiting body inhibit porcine respiratory syndrome virus infection by repressing viral entry, viral RNA expression, possibly viral protein synthesis, cell-to-cell spread, and the release of virus particles from the host cell. C. volvatus also inhibits influenza virus replication in vitro and in vivo.57,58,59

anti-viral activity through multiple mechanisms. Aqueous extracts of the fruiting body inhibit porcine respiratory syndrome virus infection by repressing viral entry, viral RNA expression, possibly viral protein synthesis, cell-to-cell spread, and the release of virus particles from the host cell. C. volvatus also inhibits influenza virus replication in vitro and in vivo.57,58,59

The aqueous extract of Phellinus igniarius, or Fire Sponge, shows virucidal activity against influenza A and B viruses, including 2009 pandemic H1N1, human H3N2, avian H9N2, and oseltamivir-resistant H1N1 viruses. The study concludes that this extract may interfere with one or more early events in the viral replication cycle, including viral attachment to the target cell. 60

In vitro research is what propels in vivo research forward, but it is important to take this information with a grain of salt and understand this is what may happen in the human body, and not necessarily what will happen.

Anti-neuraminidase activity

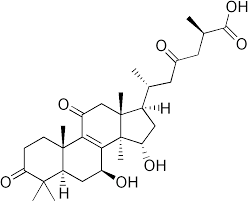

A highly valued antiviral action in pharmaceuticals is neuraminidase inhibition. This is the mechanism of the commonly known antivirals Tamilflu and Rilenza. Neuraminidase is found on the surface of influenza viruses and allows viruses to be released from the host cell so they can then infect other healthy human cells. Neuraminidase inhibitors have been shown to improve the outcome of patients with leukemia and influenza. 61 Medicinal mushrooms and their constituents have been shown to have neuraminidase

inhibitory activity in vitro and in vivo. Ganoderic acids, triterpenes found in Ganoderma species, have broad spectrum inhibition against influenza neuraminidases, specifically H5N1 andH1N1.62,63 Both the fruiting body and mycelial extracts of Phellinus spp. have neuraminidase inhibiting actions as well. 64,65,66 While there is still more research needed in this area, it is possible that Reishi and Phellinus species could be beneficial in treating viruses that utilize neuraminidase.

inhibitory activity in vitro and in vivo. Ganoderic acids, triterpenes found in Ganoderma species, have broad spectrum inhibition against influenza neuraminidases, specifically H5N1 andH1N1.62,63 Both the fruiting body and mycelial extracts of Phellinus spp. have neuraminidase inhibiting actions as well. 64,65,66 While there is still more research needed in this area, it is possible that Reishi and Phellinus species could be beneficial in treating viruses that utilize neuraminidase.

This paper focuses on mushrooms as antiviral therapies for enveloped, influenza-like viruses, but there is in vitro evidence to suggest medicinal mushrooms have antiviral activity towards many different viruses.67,68 Ganoderma lucidum has shown to be active against enterovirus, 69 human papillomavirus (HPV),70,71 herpes simplex virus (HSV)72,73,74,75 hepatitis B (HBV)76 and Epstein Barr virus (EBV).77 Cordyceps militaris has anti-hepatitis C (HCV) activity.78 Trametes versicolor is active against human immunodeficiency virus HIV.79.80 Grifola frondosa is active against HSV-181 and HBV.82 Inonotus obliquus has anti-HSV, 83,84 anti-HCV 85and anti-HIV86 activity and Lentinula edodes has anti-HBV 87 and anti-HSV 88 activity. Although not explored in this paper, these antiviral actions are interesting and worth considering for further dissection in future research.

Having a basic understanding of our complex immune system is important in understanding the role that mushrooms play as antivirals. As we have seen, mushrooms are immune modulators and can stimulate inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses simultaneously. Mushrooms are most likely to be useful as preventative medicine before infection occurs, though if there is an initial infection, Cordyceps, Maitake, Shiitake, Turkey tail and Oyster mushroom may prevent infection from becoming more severe. If infection does become severe, the mushrooms that also stimulate IL-10 – Maitake, Cordyceps and Shiitake, could also be beneficial. In the wake of the current viral pandemic, these mushrooms should be further explored and utilized as medicine. Further research is essential in elucidating their potential effects.

Work cited

- “Innate Immunity: the Induced Response to Infection.” The Immune System, by Peter Parham, Garland Science, 2015, pp. 68–78.

- Jost S, Altfeld M. Control of Human Viral Infections by Natural Killer Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31(1):163-194. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-100001

- Vidal, Sylvia M. Khakoo, SalminI. Biron CA. Natural Killer Cell Responses during Viral Infections: Flexibility and Conditioning of Innate Immunity by Experience. 2011;1(6):497-512. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2011.10.017.Natural

- Waggoner, Stephen N. Reighard, Seth D., Gyurova IE et al. Roles of natural killer cells in antiviral immunity. Curr Opin Virol. 2016;16:15-23. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.03.040

- Shi Y, Wang Y, Shao C, Huang J, Gan J, Huang X. COVID-19 infection : the perspectives on immune responses. Cell Death Differ. 2020. doi:10.1038/s41418-020-0530-3

- Liu CH, Kuo SW, Ko WJ, et al. Early measurement of IL-10 predicts the outcomes of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1-10. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01225-1

- Van Erp EA, Van Kampen MR, Van Kasteren PB, De Wit J. Viral infection of human natural killer cells. Viruses. 2019;11(3):1-13. doi:10.3390/v11030243

- Kang, Ho Joon, Baik, Hyun Wook KSJ et al. Cordyceps militaris Enhances Cell-Mediated Immunity in Healthy Korean Men. 2015;18(October 2014):1164-1172. doi:10.1089/jmf.2014.3350

- Jung SJ, Jung ES, Choi EK, Sin HS, Ha KC, Chae SW. Immunomodulatory effects of a mycelium extract of Cordyceps (Paecilomyces hepiali; CBG-CS-2): A randomized and double-blind clinical trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19(1):1-8. doi:10.1186/s12906-019-2483-y

- Zhu L, Tang Q, Zhou S, et al. Isolation and purification of a polysaccharide from the caterpillar medicinal mushroom Cordyceps militaris (Ascomycetes) fruit bodies and its immunomodulation of RAW 264.7 macrophages. Int J Med Mushrooms. 2014;16(3):247–257. doi:10.1615/intjmedmushr.v16.i3.50

- Lee JS, Hong EK. Immunostimulating activity of the polysaccharides isolated from Cordyceps militaris. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11(9):1226–1233. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2011.04.001

- Wang M, Meng XY, Yang RL, et al. Cordyceps militaris polysaccharides can enhance the immunity and antioxidation activity in immunosuppressed mice. Carbohydr Polym. 2012;89(2):461–466. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.03.029

- Dai X, Stanilka JM, Rowe CA, et al. Consuming Lentinula edodes (Shiitake) Mushrooms Daily Improves Human Immunity: A Randomized Dietary Intervention in Healthy Young Adults. J Am Coll Nutr. 2015;34(6):478-487. doi:10.1080/07315724.2014.950391

- Deng G. A phase I/II trial of a polysaccharide extract from Grifola frondosa in breast cancer patients inmunological effects. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;135(9):1215-1221. doi:10.1007/s00432-009-0562-z.A

- Wong CK, Tse PS, Wong ELY, Leung PC, Fung KP, Lam CWK. Immunomodulatory effects of Yun Zhi and Danshen capsules in health subjects – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Int Immunopharmacol. 2004;4(2):201-211. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2003.12.003

- Gaullier J-M, Sleboda J, Øfjord ES, et al. Supplementation with a soluble β-glucan exported from Shiitake medicinal mushroom, Lentinus edodes (Berk.) singer mycelium: a crossover, placebo-controlled study in healthy elderly. Int J Med Mushrooms. 2011;13(4):319-326. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22164761. Accessed June 10, 2019.

- Hetland G, Johnson E, Lyberg T, Kvalheim G. The mushroom Agaricus blazei murill elicits medicinal effects on tumor, infection, allergy, and inflammation through its modulation of innate immunity and amelioration of Th1/Th2 imbalance and inflammation. Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2011;2011(Figure 2). doi:10.1155/2011/157015

- Cui L, Sun Y, Xu H, Xu H, Cong H, Liu J. A polysaccharide isolated from Agaricus blazei Murill (ABP-AW1) as a potential Th1 immunity-stimulating adjuvant. Oncol Lett. 2013;6(4):1039-1044. doi:10.3892/ol.2013.1484

- Lima CUJO, Souza VC, Morita MC, Chiarello MD, Karnikowski MGDO. Agaricus blazei Murrill and Inflammatory Mediators in Elderly Women : A Randomized Clinical Trial. 2011:336-342. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3083.2011.02656.x

- O’Garra A, Vieira PL, Vieira P, Goldfeld AE. IL-10-producing and naturally occurring CD4+ Tregs: limiting collateral damage. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(10):1372–1378

- Couper KN, Blount DG, Riley EM. IL-10: the master regulator of immunity to infection. J Immunol. 2008;180(9):5771–5777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawrylowicz CM. Regulatory T cells and IL-10 in allergic inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;202(11):1459–1463

- Wu K, Bi Y, Sun K, Wang C. IL-10-producing type 1 regulatory T cells and allergy. Cell Mol Immunol. 2007;4(4):269–275

- Rojas JM, Avia M, Martín V, Sevilla N. IL-10: A multifunctional cytokine in viral infections. J Immunol Res. 2017;2017. doi:10.1155/2017/6104054

- Liu CH, Kuo SW, Ko WJ, et al. Early measurement of IL-10 predicts the outcomes of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1-10. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01225-1

- Fang J, Wang Y, Lv X. Structure of a β -glucan from Grifola frondosa and its antitumor effect by activating Dectin-1 / Syk / NF- κ B signaling. 2012:365-377. doi:10.1007/s10719-012-9416-z

- Akramienė, Dalia, Kondrotas, Anatolijus Didžiapetrienė J et al. Effects of B-glucans on the immune system. Medicina (B Aires). 2007;43(8). doi:10.4271/911515

- Charlton CL, Babady E, Ginocchio CC, Hatchette TF, Jerris RC, Li Y, Loeffelholz M, McCarter YS, Miller MB, Novak-Weekley S, Schuetz AN, Tang Y-W, Widen R, Drews SJ. 2019. Practical guidance for clinical microbiology laboratories: viruses causing acute respiratory tract infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 32:e00042-18. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR .00042-18.

- Jesenak M, Hrubisko M, Majtan J, Rennerova Z, Banovcin P. Anti-allergic Effect of Pleuran ( b -glucan from Pleurotus ostreatus ) . Jesenak M, Urbanclkova I, Banovcin P. Respiratory Tract Infections and the Role of Biologically Active Polysaccharides in Their. Nutrients. 2017:1-12. doi:10.3390/nu9070779 in Children with Recurrent Respiratory Tract Infections. 2014;474(March 2013):471-474.

- Pico Sirvent L, Sapena Grau J, Morera Ingles M, Rivero Urgell M. Effect of supplementation with β–glucan from Pleurotus ostreatus in children with recurrent respiratory infections. Ann Nurr Metab. 2013; 63 (1): 1378

- Bergendiova K, Tibenska E. Pleuran ( b -glucan from Pleurotus ostreatus ) supplementation , cellular immune response and respiratory tract infections in athletes. 2011:2033-2040. doi:10.1007/s00421-011-1837-z.

- McCleary B V., Draga A. Measurement of β-Glucan in mushrooms and mycelial products. J AOAC Int. 2016;99(2):364-373. doi:10.5740/jaoacint.15-0289

- Gao Y, Tang W, Dai X, et al. Effects of water-soluble Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides on the immune functions of patients with advanced lung cancer. J Med Food. 2005;8(2):159-168. doi:10.1089/jmf.2005.8.159

- Torkelson CJ, Sweet E, Martzen MR, et al. Phase 1 Clinical Trial of Trametes versicolor in Women with Breast Cancer. Int Sch Res Netw. 2012;2012. doi:10.5402/2012/251632

- Kodama N, Komuta K, Nanba H. Activation of NK Cells in Cancer Patients. 2003;6(4):371-377.

- Müller L, Aigner P, Stoiber D. Type I interferons and natural killer cell regulation in cancer. Front Immunol. 2017;8(MAR):1-11. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.00304

- Mb YY, Fu W, Fu M, He G, Traore L. The immune effects of edible fungus polysaccharides compounds in mice. 2007;16(Suppl l):258-260.

- Vetvicka V, Vetvickova J. Immune-enhancing effects of Maitake (Grifola frondosa) and Shiitake (Lentinula edodes) extracts. Ann Transl Med.2014;2(2):14. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.01.05

- Noriko Kodama Yukihito Murata Hiroaki Nanba. Administration of a Polysaccharide from Grifola frondosa Stimulates Immune Function of Normal Mice Noriko. 2004;7(2):141-145.

- Lee HH, Park H, Sung GH, et al. Anti-influenza effect of Cordyceps militaris through immunomodulation in a DBA/2 mouse model. J Microbiol. 2014;52(8):696-701. doi:10.1007/s12275-014-4300-0

- Takimoto H, Kato H, Kaneko M, Kumazawa Y. Amelioration of skewed Th1/ Th2 balance in tumor-bearing and asthma-induced mice by oral administra- tion of Agaricus blazei extracts. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2008;30(4):747-760.

- Lin JG, Fan MJ, Tang NY, et al. An extract of Agaricus blazei Murill adminis- tered orally promotes immune responses in murine leukemia BALB/c mice in vivo. Integr Cancer Ther. 2012;11(1):29-36.

- Zhang S, Nie S, Huang D, Li W, Xie M. Immunomodulatory effect of Ganoderma atrum polysaccharide on CT26 tumor-bearing mice. Food Chem. 2013;136(3-4):1213-1219.

- Wang G, Zhao J, Liu J, Huang Y, Zhong JJ, Tang W. Enhancement of IL-2 and IFN-gamma expression and NK cells activity involved in the anti-tumor effect of ganoderic acid Me in vivo. Int Immunopharmacol. 2007;7(6):864- 870.

- Wang PY, Zhu XL, Lin ZB. Antitumor and immunomodulatory effects of polysaccharides from broken-spore of Ganoderma lucidum. Front Pharmacol. July 2012;3:135.

- Wang G, Zhao J, Liu J, Huang Y, Zhong J-J, Tang W. Enhancement of IL-2 and IFN-γ expression and NK cells activity involved in the anti-tumor effect of ganoderic acid Me in vivo. Int Immunopharmacol. 2007;7(6):864-870. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2007.02.006

- Kodama N, Mizuno S, Nanba H, Saito N. Potential antitumor activity of a low-molecular-weight protein fraction from Grifola frondosa through enhancement of cytokine production. J Med Food. 2010;13(1):20-30. doi:10.1089/jmf.2009.1029

- Masuda Y, Murata Y, Hayashi M, Nanba H. Inhibitory effect of MD-Fraction on tumor metastasis: involvement of NK cell activation and suppression of intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 expression in lung vascular endothelial cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008;31(6):1104–1108. doi:10.1248/bpb.31.1104

- Lu H, Yang Y, Gad E, et al. TLR2 agonist PSK activates human NK cells and enhances the antitumor effect of HER2-targeted monoclonal antibody therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(21):6742–6753. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1142

- Zhu XL, Chen AF, Lin Z Bin. Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides enhance the function of immunological effector cells in immunosuppressed mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;111(2):219-226. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2006.11.013

- Wang C, Wang Y. Abstracts from the 2nd International Symposium on Phytochemicals in Medicine and Food (2-ISPMF). Chin Med. 2018;13(S1):1-63. doi:10.1186/s13020-018-0172-2

- Linnakoski R, Reshamwala D, Veteli P, Cortina-Escribano M, Vanhanen H, Marjomäki V. Antiviral agents from fungi: Diversity, mechanisms and potential applications. Front Microbiol. 2018;9(OCT). doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.02325

- Ho CY, Lau CBS, Kim CF, et al. Differential effect of Coriolus versicolor (Yunzhi) extract on cytokine production by murine lymphocytes in vitro. Int Immunopharmacol. 2004;4(12):1549-1557. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2004.07.021

- Jeong SC, Yang BK, Kim GN, et al. Macrophage-stimulating activity of polysaccharides extracted from fruiting bodies of Coriolus versicolor (Turkey tail mushroom). J Med Food. 2006;9(2):175-181. doi:10.1089/jmf.2006.9.175

- Obi N, Hayashi K, Miyahara T, et al. Inhibitory effect of TNF-α produced by macrophages stimulated with Grifola frondosa extract (ME) on the growth of influenza A/Aichi/2/68 Virus in MDCK cells. Am J Chin Med. 2008;36(6):1171-1183. doi:10.1142/S0192415X08006508

- Kuroki T, Lee S, Hirohama M, et al. Inhibition of Influenza Virus Infection by Lentinus edodes Mycelia Extract Through Its Direct Action and Immunopotentiating Activity. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1164. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.01164

- Gao L, Sun Y, Si J, et al. Cryptoporus volvatus extract inhibits influenza virus replication in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 2014;9(12). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0113604

- Gao L, Zhang W, Sun Y, et al. Cryptoporus volvatus Extract Inhibits Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus (PRRSV) In Vitro and In Vivo. PLoS One. 2013;8(5). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063767

- Ma Z, Zhang W, Wang L, et al. A novel compound from the mushroom Cryptoporus volvatus inhibits porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) in vitro. PLoS One. 2013;8(11). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079333

- Lee S, Kim JI, Heo J, et al. The anti-influenza virus effect of Phellinus igniarius extract. J Microbiol. 2013;51(5):676–681. doi:10.1007/s12275-013-3384-2

- Chemaly RF, Torres HA, Aguilera EA, et al. Neuraminidase Inhibitors Improve Outcome of Patients with Leukemia and Influenza: An Observational Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(7):964-967. doi:10.1086/512374

- Zhu Q, Bang TH, Ohnuki K, Sawai T, Sawai K, Shimizu K. Inhibition of neuraminidase by Ganoderma triterpenoids and implications for neuraminidase inhibitor design. Sci Rep. 2015;5(AUGUST):13194. doi:10.1038/srep13194

- Zhu T, Kim S-H, Chen C-Y. A Medicinal Mushroom: Phellinus Linteus. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15(13):1330-1335. doi:10.2174/092986708784534929

- Kim J, Kim D, Hwang BS, et al. Mycobiology Neuraminidase Inhibitors from the Fruiting Body of Phellinus igniarius. 2016:117-120.

- Yeom JH, Lee IK, Ki DW, Lee MS, Seok SJ, Yun BS. Neuraminidase inhibitors from the culture broth of Phellinus linteus. Mycobiology.2012;40(2):142-144. doi:10.5941/MYCO.2012.40.2.142

- Song AR, Sun XL, Kong C, et al. Discovery of a new sesquiterpenoid from Phellinus ignarius with antiviral activity against influenza virus. Arch Virol. 2014;159(4):753–760. doi:10.1007/s00705-013-1857-6

- Teplyakova T V. antiviral activity of polyporoid mushrooms (higher basidiomycetes) from Altai Mountains (Russia). 2012:37-45.

- Krupodorova T, Rybalko S, Barshteyn V. Antiviral activity of Basidiomycete mycelia against influenza type A (serotype H1N1) and herpes simplex virus type 2 in cell culture. Virol Sin. 2014;29(5):284-290. doi:10.1007/s12250-014-3486-y

- Zheng DS, Chen LS. Triterpenoids from Ganoderma lucidum inhibit the activation of EBV antigens as telomerase inhibitors. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14(4):3273-3278. doi:10.3892/etm.2017.4883

- Hernández-Márquez E, Lagunas-Martínez A, Bermudez-Morales VH, et al. Inhibitory activity of Lingzhi or Reishi medicinal mushroom, Ganoderma lucidum (higher Basidiomycetes) on transformed cells by human papillomavirus. Int J Med Mushrooms. 2014;16(2):179–187. doi:10.1615/intjmedmushr.v16.i2.80

- Donatini B. Control of oral human papillomavirus (HPV) by medicinal mushrooms, Trametes versicolor and Ganoderma lucidum: a preliminary clinical trial. Int J Med Mushrooms. 2014;16(5):497–498. doi:10.1615/intjmedmushrooms.v16.i5.80

- Eo SK, Kim YS, Lee CK, Han SS. Possible mode of antiviral activity of acidic protein bound polysaccharide isolated from Ganoderma lucidum on herpes simplex viruses. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;72(3):475–481. doi:10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00266-x

- Oh KW, Lee CK, Kim YS, Eo SK, Han SS. Antiherpetic activities of acidic protein bound polysacchride isolated from Ganoderma lucidum alone and in combinations with acyclovir and vidarabine. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;72(1-2):221–227. doi:10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00254-3

- Hijikata Y, Yamada S, Yasuhara A. Herbal mixtures containing the mushroom Ganoderma lucidum improve recovery time in patients with herpes genitalis and labialis. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(9):985–987. doi:10.1089/acm.2006.6297

- Eo SK, Kim YS, Lee CK, Han SS. Antiherpetic activities of various protein bound polysaccharides isolated from Ganoderma lucidum. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;68(1-3):175–181. doi:10.1016/s0378-8741(99)00086-0

- Li YQ, Wang SF. Anti-hepatitis B activities of ganoderic acid from Ganoderma lucidum. Biotechnol Lett. 2006;28(11):837–841. doi:10.1007/s10529-006-9007-9

- Iwatsuki K, Akihisa T, Tokuda H, et al. Lucidenic acids P and Q, methyl lucidenate P, and other triterpenoids from the fungus Ganoderma lucidum and their inhibitory effects on Epstein-Barr virus activation. J Nat Prod. 2003;66(12):1582–1585. doi:10.1021/np0302293

- Ueda Y, Mori K, Satoh S, Dansako H, Ikeda M, Kato N. Anti-HCV activity of the Chinese medicinal fungus Cordyceps militaris. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;447(2):341–345. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.03.150

- Rodríguez-Valentín M, López S, Rivera M, Ríos-Olivares E, Cubano L, Boukli NM. Naturally Derived Anti-HIV Polysaccharide Peptide (PSP) Triggers a Toll-Like Receptor 4-Dependent Antiviral Immune Response. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:8741698. Published 2018 Jul 15. doi:10.1155/2018/8741698

- Collins RA, Ng TB. Polysaccharopeptide from Coriolus versicolor has potential for use against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Life Sci. 1997;60(25):PL383–PL387. doi:10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00294-4

- Gu C, Li J, Chao F, Jin M, Wang X, Shen Z. Isolation , identification and function of a novel anti-HSV-1 protein from Grifola frondosa. 2007;75:250-257. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.03.011

- Gu CQ, Li J, Chao FH. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus by D-fraction from Grifola frondosa: synergistic effect of combination with interferon-alpha in HepG2 2.2.15 [published correction appears in Antiviral Res. 2007 Jul;75(1):91. Li, Jun-Wen [corrected to Li, JunWen]]. Antiviral Res. 2006;72(2):162–165. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.05.011

- Polkovnikova MV, Nosik NN, Garaev TM, Kondrashina NG, Finogenova MP, Shibnev VA. Vopr Virusol. 2014;59(2):45–48.

- Pan HH, Yu XT, Li T, et al. Aqueous extract from a Chaga medicinal mushroom, Inonotus obliquus (higher Basidiomycetes), prevents herpes simplex virus entry through inhibition of viral-induced membrane fusion. Int J Med Mushrooms. 2013;15(1):29–38. doi:10.1615/intjmedmushr.v15.i1.40

- Shibnev VA, Mishin DV, Garaev TM, Finogenova NP, Botikov AG, Deryabin PG. Antiviral activity of Inonotus obliquus fungus extract towards infection caused by hepatitis C virus in cell cultures. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2011;151(5):612–614. doi:10.1007/s10517-011-1395-8

- Shibnev VA, Garaev TM, Finogenova MP, Kalnina LB, Nosik DN. Vopr Virusol. 2015;60(2):35–38.

- Zhao YM, Yang JM, Liu YH, Zhao M, Wang J. Ultrasound assisted extraction of polysaccharides from Lentinus edodes and its anti-hepatitis B activity in vitro. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;107(Pt B):2217–2223. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.10.100

- Santoyo,Susana, Ramirez-Anguiana Ana, christina Aldaris-Garcia L et al. Antiviral activities of Boletus edulis, Pleurotus ostreatus and Lentinus edodes extracts and polysaccharide fractions against Herpes simplex virus type 1. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;88(12):4. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.126404

(Red sage root, or Dan Shen) given at 50mg/kg and 20mg/kg respectively for four months showed significant immunomodulatory effects in healthy adults. There was a significant increase in PBMC (peripheral blood mononuclear cells – NK, B and T cells) gene expression of IL-2 receptor, increase in T helper cells and the ratio of T helper cells to cytotoxic T cells. There is also a significant increase in IFN-γ.15 There is little information in western herbal and mycological medicine about the use of plant and mushroom combination formulas. Dan Shen is known to ‘move the qi of the blood’ and in combination with the immune stimulating activity of Turkey tail, has promise as a very useful combination for immune therapy.

(Red sage root, or Dan Shen) given at 50mg/kg and 20mg/kg respectively for four months showed significant immunomodulatory effects in healthy adults. There was a significant increase in PBMC (peripheral blood mononuclear cells – NK, B and T cells) gene expression of IL-2 receptor, increase in T helper cells and the ratio of T helper cells to cytotoxic T cells. There is also a significant increase in IFN-γ.15 There is little information in western herbal and mycological medicine about the use of plant and mushroom combination formulas. Dan Shen is known to ‘move the qi of the blood’ and in combination with the immune stimulating activity of Turkey tail, has promise as a very useful combination for immune therapy.

of 50 athletes treated with pleuran over a three month period found a significant reduction in the frequency of upper respiratory tract infections compared to athletes treated with placebo. Blood samples of the athletes showed significantly higher levels of circulating NK cells in the pleuran group as compared to the placebo group.31

of 50 athletes treated with pleuran over a three month period found a significant reduction in the frequency of upper respiratory tract infections compared to athletes treated with placebo. Blood samples of the athletes showed significantly higher levels of circulating NK cells in the pleuran group as compared to the placebo group.31 anti-viral activity through multiple mechanisms. Aqueous extracts of the fruiting body inhibit porcine respiratory syndrome virus infection by repressing viral entry, viral RNA expression, possibly viral protein synthesis, cell-to-cell spread, and the release of virus particles from the host cell. C. volvatus also inhibits influenza virus replication in vitro and in vivo.57,58,59

anti-viral activity through multiple mechanisms. Aqueous extracts of the fruiting body inhibit porcine respiratory syndrome virus infection by repressing viral entry, viral RNA expression, possibly viral protein synthesis, cell-to-cell spread, and the release of virus particles from the host cell. C. volvatus also inhibits influenza virus replication in vitro and in vivo.57,58,59

inhibitory activity in vitro and in vivo. Ganoderic acids, triterpenes found in Ganoderma species, have broad spectrum inhibition against influenza neuraminidases, specifically H5N1 and

inhibitory activity in vitro and in vivo. Ganoderic acids, triterpenes found in Ganoderma species, have broad spectrum inhibition against influenza neuraminidases, specifically H5N1 and